History

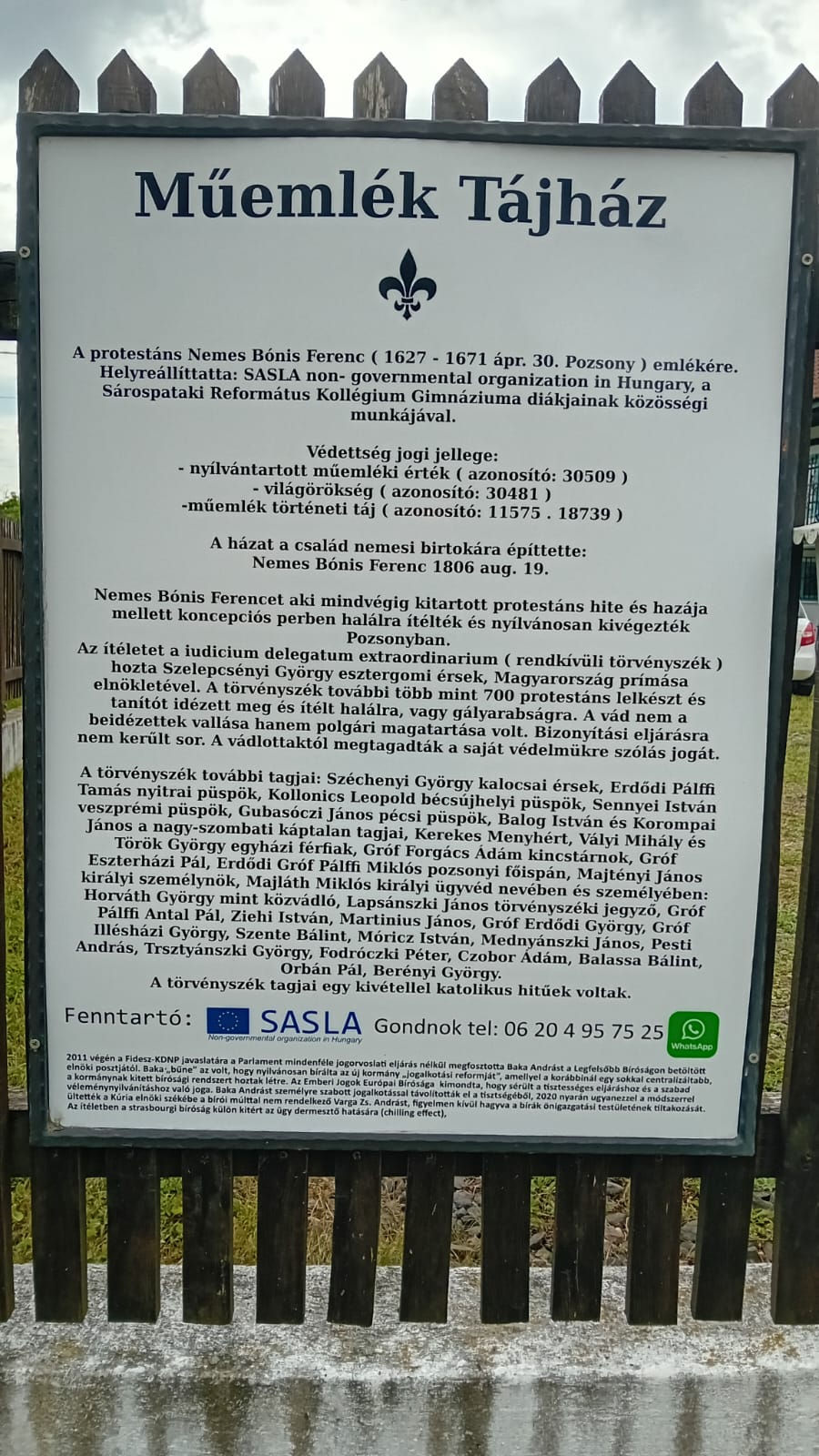

The Erdőhorváti Heritage House is a vernacular residential building constructed in the 17th century on a noble estate, closely connected to the Nemes Bónis family. In the local and regional historical memory, this house represents not only architectural value but also the struggle for freedom, faith, and community solidarity.

1. Legacy of Ferenc Nemes Bónis

The founder and namesake of the house, Ferenc Nemes Bónis (1627–1671), remained loyal to his Protestant faith and homeland throughout his life, which led to his death sentence in a show trial and public execution in Pozsony (Bratislava). The accusations were baseless, and the defendants were denied the right to defense. Over 700 Protestant pastors and teachers were sentenced to death or galley slavery under ecclesiastical and secular pressure.

This brutal procedure – conducted by the extraordinary court led by György Szelepcsényi, Archbishop of Esztergom – revealed the nature of power: the suppression of freedom and free religious practice.

2. Parallels and Memory Politics

Bónis Ferenc’s story remains instructive today. Authorities often attempt to erase traces of tyranny and oppression. In Erdőhorváti, local officials initially wanted to replace the house with a paved park. The original plan was demolition, but the village representatives neither recognized their cultural heritage nor the house’s symbolic significance.

Thanks to community efforts by SASLA NGO and students of the Sárospatak Reformed College High School, the house was preserved and designated as a protected heritage site. It is now officially registered as:

- Registered Heritage Property (ID: 30509)

- Part of World Heritage (ID: 30481)

- Historical Landscape Heritage (IDs: 11575, 18739)

3. Protestants and Jewish Communities

The Bónis family and other Protestant nobles often supported local Jewish communities. There is a shared experience of persecution for both groups due to religious and social reasons. The Protestants’ support for Jews serves as an enduring example of solidarity and joint resistance against arbitrary power.

4. European Context and Historical Connections

The Protestant pastors sentenced to galley slavery were eventually aided by the Dutch navy under the famous Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. This early example of international cooperation aimed to protect freedom and human dignity.

The Wesselényi conspiracy and the era of the Rákóczi family highlight how the Jesuits and other powers attempted to rewrite history: heroes were often overshadowed, while those who compromised were celebrated. Consequently, while the memory of the Rákóczis survives in Sárospatak, Ferenc Bónis’ brave stand remained unjustly forgotten.

5. Modern Parallels and Message

The story is not over. Mechanisms of authoritarianism are still recognizable: critics are silenced, communal values are appropriated, and inconvenient witnesses of the past are erased. The initial municipal demolition plan illustrates how the logic of power has not changed.

Legislative centralization, control over courts, and suppression of dissent – as highlighted in the European Court of Human Rights case of András Baka – represent modern forms of “show trials.”

6. Summary

The Erdőhorváti Heritage House is not merely an old vernacular building. It serves as a reminder and warning that freedom must always be defended because power repeatedly tempts oppression.

The lessons of the past – Bónis Ferenc’s martyrdom, the Protestant pastors’ galley slavery, the persecution of Jewish communities – resonate with current challenges. The building’s preservation proves that civil courage and community solidarity can withstand forces of oblivion and destruction.